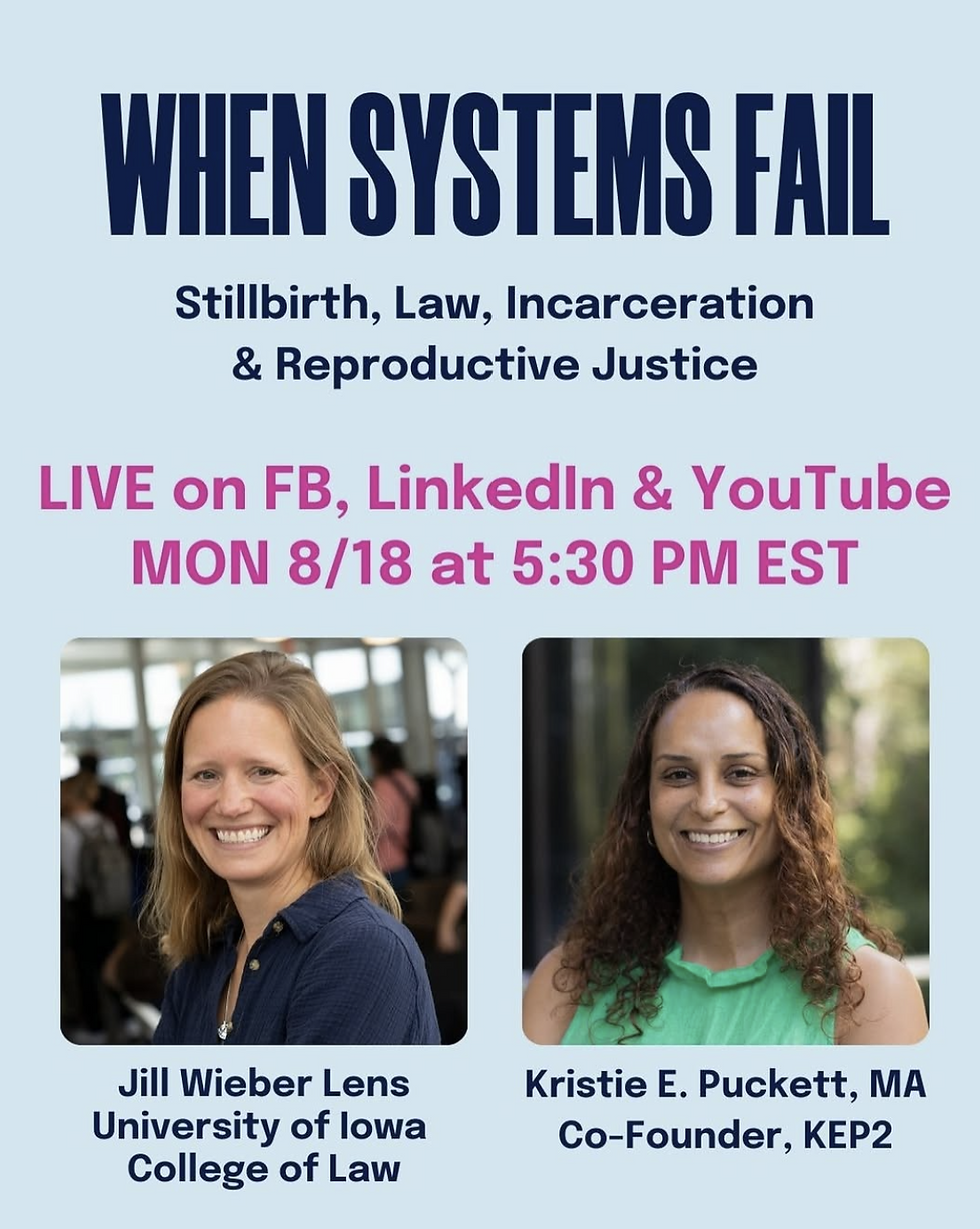

When Systems Fail: Stillbirth, Law, Incarceration & Repro Justice

- Official PUSH Blog

- Aug 18, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 21, 2025

PUSH is bringing together two incredible voices to explore the intersection of stillbirth, law, incarceration during pregnancy, reproductive justice, and systemic racism.

Hear more below from Jill Wieber Lens, stillbirth mom, PUSH Board Member, law professor, and author of Stillbirth & the Law, and Kristie Puckett — policy strategist, gender & racial justice advocate, and formerly incarcerated mother who has shared her powerful lived experience nationally.

Also don't miss the powerful Live discussion on our YouTube, Facebook and LinkedIn pages to hear how legal systems, healthcare, and the carceral system collide to shape pregnancy outcomes — and what we can all do to fight for change.

From Professor Jill Lens:

My name is Jill Lens. I’m a law professor and a Board member of PUSH. I’m also a proud PUSH Changemaker. My son Caleb was stillborn just over 8 years ago when I was 37 weeks pregnant.

Since his death, I’ve blended my personal and professional life, focusing my research on how laws affect stillbirth. When I first started, I wasn’t sure I’d have much to research. That was naïve. There’s so much to talk about, in fact, that I was fortunate to recently publish a book entitled "Stillbirth & the Law." Broadly, the book explores how federal and state laws are 1) contributing to the U.S.’s alarming and stagnant stillbirth rate, 2) affecting the lived experience of stillbirth, and 3) shaping broader ideas about unborn life.

I’d like to share two examples of content from the book. The first is a discrepancy within ACOG and SMFM’s guidelines on care in pregnancies high-risk for stillbirth. As you likely know, ACOG and SMFM lack guidelines aimed at preventing stillbirth in low-risk pregnancies (whereas other countries do). They do have guidelines, however, for known high-risk pregnancies, defined as when the risk of stillbirth is double. One of those conditions where the risk of stillbirth is double is for pregnancies conceived with in vitro fertilization, and the guidelines recommend additional surveillance aimed at preventing stillbirth for those pregnancies.

Another condition for which the risk of stillbirth is double is if the pregnant person is a Black woman. The ACOG and SMFM high-risk guideline admits this. But it specifically does not recommend additional care despite the known doubled risk. Instead, it states "until further data are available on the effects of specific factors resulting from racism, recommendations regarding fetal surveillance cannot be made." The Guideline was first published in 2021 and reaffirmed in 2024 (without changes to this language). In short, most often White women who can actually afford IVF get additional surveillance aimed at preventing stillbirth. The Black women who have the same double risk, not so much.

The second content relates to an experience too many of us have had — not knowing anything about the possibility of stillbirth until after our child died. I discuss this experience from the context of informed consent, a law and ethical principle that aims to remedy the knowledge disparity between doctors and patients. Why don’t doctors talk about stillbirth ahead of time?

The reasons include: the rarity (false), that it would cause unnecessary anxiety (paternalistic and likely false), economic disincentives in that doctors won’t be compensated for anxiety-driven doctor’s visits (exaggerating the likelihood of the visits), and the assumption of inevitability of stillbirth (false). Notably, both the law and ethical principle specifically limit this idea of non-disclosure because of anxiety; the point is to empower the patient with information, not tell her only what doctors think she needs to know.

Plus, the benefits of disclosure of stillbirth are underestimated. It could lessen the shock and possibly decrease the alienation and stigma many of us feel. It would likely lessen the inclination to question and blame the doctor. And it could be extremely helpful in emergency situations where patients often think the doctor is being coercive when he brings up stillbirth (for the first time) in advising the patient on a procedure. Not talking about stillbirth isn’t going to prevent it; there really is little if any benefit to keeping pregnant people in the dark.

This book is inspired by my son, obviously, but also by the inspiring stillbirth parents I have met within advocacy and support efforts. I’m especially grateful to the stillbirth parents who let me share their stories in the book. I hope that the book helps explain why certain things are the way they are — and that it offers some suggestions for change that could prevent future stillbirths and make things better for those who still do give birth to their stillborn child.

You can also read the introduction of the book (and meet my Caleb) here https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5220120.

Jill's book is available at the traditional retailers. You can also order it direct from the publisher UC Press at https://www.ucpress.edu/books/stillbirth-and-the-law/paper with the coupon UCPSAVE for 30% off.

Excerpt from an article by Kristie Puckett, MA: code UCPSAVE

The use of solitary confinement for incarcerated pregnant people is an indefensible and cruel practice. Unfortunately, it’s more common than you might think.

In many cases, there are more legal protections and oversights concerning the protection of captive wild animals and the care and handling of farm animals then there are for incarcerated pregnant people in the United States. In Colorado, for example, a pregnant pig cannot be confined to a cage for more than 12 hours a day. But in most states, no such protections exist for pregnant people.

Solitary confinement refers to confinement in a cell for all or nearly all of the day—resulting in deprivation of meaningful social contact, physical activity and environmental stimulation. Solitary confinement of any length, but particularly prolonged solitary confinement for more than 15 days, can cause serious emotional, psychological and physical harm to people, especially vulnerable populations such as those who are pregnant or have mental illness.

This harm is not just theoretical. A number of pregnant women, including a seriously mentally ill pretrial detainee, have been forced to give birth alone while in solitary confinement. The psychological torture of solitary confinement, the inability to access sufficient exercise or nutrition and the impediments to accessing necessary care combine to place pregnant people in solitary confinement at serious risk.

Continue reading at https://msmagazine.com/2019/10/23/pregnant-women-in-north-carolina-prisons-are-being-kept-in-solitary-confinement/

Don't miss the Live discussion PUSH's YouTube, Facebook and LinkedIn pages! #UnitedWePush